The state of affairs described below is not unique to Malta but the size of the country and the physical proximity of its different elements makes it more obvious.

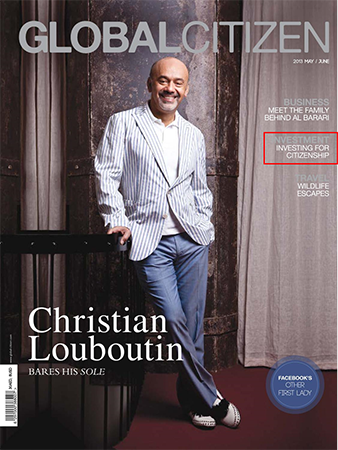

In a nutshell, the terms ‘expat’ and ‘migrant’ echo the profound class and racial inequality which is still present in the world. ‘Expat’ is usually reserved for an individual from the EU&Co, North America and Australia who left his native country for work in a multinational company or for leisure. ‘Global citizen’ describes the specific, most privileged kind of expat, who sees the world “without borders” because the borders literally do not exist for him. The advantages of his golden passport and the financial assets spare him from the humiliating struggles for the freedom of movement.

A migrant, on the other hand, is everyone else who leaves his place of birth in search of a better life. A migrant only aspires to become a global citizen because his opportunities for re-settlement are institutionally restricted. ‘Refugee’ is the most disadvantaged kind of arrival: his resettlement is not driven by the free will but is forced upon him by war, natural disasters and/or extreme poverty.

‘Global citizens’, migrants and refugees do not receive an equal treatment. In fact, the treatment they receive directly corresponds to their status. Where a wealthy expat is greeted with an open gate, a migrant finds endless bureaucracy and a refugee – a barbed wire. For instance, this inequality of treatment was exposed by the favourable attention to the insensitive rant of the white, privileged, proud-to-be-expat Canadian who labelled Malta a “developing country”. Unsurprisingly, many Maltese swallowed the offence with resignation. Too many just nodded with embarrassment, apologising for the lack of sleek sophistication they could offer to such a distinguished guest.

***

While some expats bathe in public attention, homeless migrants die in poverty. The three-paragraphs-short articles reported the tragic events in a plain and casual manner, stating that one migrant was found dead under the bridge and the other – in a games room at Xatt il-Mollijiet in Marsa. Both Somali men came from afar only to find their lonely death in Malta. They left their native countries but poverty stayed with them until the very end.

While a refugee and a migrant constantly live in fear of deportation and repercussions, a wealthy ‘global citizen’ is welcomed with open arms and with the exclusive offer of a Maltese passport (if he happens to need one). On the other hand, a refugee is unwelcome: due to an alleged mysterious deal between Italy and Malta, a few refugees disembark here.

While refugees risk their lives and constantly battle the exhausting bureaucracy for a better life in Malta, the fat-walletted expats claim that the country is not good enough for them. Isn’t it profoundly disrespectful to wave the privileges and the superior demands in front of those to whom these privileges are out of reach?

Just like the natives, expats and migrants often complain about the treatment they receive in Malta – but they do so in a different manner and for very different reasons. When a privileged expat complains about Malta, he implies that the country fails to meet his exclusive demands, suitable for his high rank. A migrant (myself included) complains about the frustrating experience which obtaining of a residence permit involves. Anyone is likely to derail having to battle for their rights on a day-to-day basis, yet the luxury of the “hassle-free residency” do not stop a wealthy expat from expressing his constant dissatisfaction. The migrant’s complaints are the cries of distress whereas those of a privileged expat are a means of morally instructing the locals.

***

Overall, migrants contribute to their new home country much more than do the ‘global citizens’. Migrants perform the most necessary jobs – care taking, nursing, cleaning. If employed by the local companies, migrants pay their tax in Malta and contribute to the Social Security funds. An ordinary migrant is not too different from an ordinary local. All he aspires to is a secure job and a stable, decent quality of life.

The privileged expat hops from one country to the other with a mission to verify whether or not the many dots on the world map live up to his expectations. He wishes to customise every country according to his demands. He has no interest in participating in the celebratory, eccentric and often absurd spectacle of life which makes Malta so special.

Integrating into a foreign society is below a ‘global citizen’. He has the whole world to cater for his demands – and everybody seems eager to respect his privilege. Yet, concerns on integration immediately raise when migrants and refugees happen to pursue their cultural habits. In fact, the cultural particularities of migrants and refugees are always blamed on their ‘lack of civilisation’ while the disdainful attitudes of ‘global citizens’ are excused for their superiority.

***

Migrants are part of the crowd and for that reason they are visible. A crime committed by a migrant causes an outrage and quickly leads to an anti-migration movement. Though much more grave, the crimes of a ‘global citizen’ are invisible to the majority. These crimes are executed in an elegant, quiet manner: tax evasion, tax avoidance and shady business investments to mention a few.

The crimes of a global citizen are legalized. He prides his intelligence for tax avoidance and that is why he specifically chooses Malta to save – not spend! – money. While most of the inferior mortals – migrants and natives alike – are struggling to keep up with the soaring high rent, more luxurious property is designed to lure the ‘global citizens’ into the country. The luxurious apartments are built by the migrants for the expats to benefit a few tycoons.

A ‘global citizen’ rejects the blame for being the cause of global inequality. He pretends to be a charitable philanthropist. The facts, however, prove the opposite: the recent research has established that the wealthy investors extract more profit from the poorer countries than vise versa. They set foot in a country to take – not give – money.

***

The new luxurious development projects in Malta are not designed for the ordinary Maltese and neither they are affordable to the migrants. Have a look at this website to see who owns the country. Malta is being given on a plate to the wealthy ‘global citizens’ – to that same cast of the privileged who call it a “developing country” and come here for “sun and the low tax”. And if the economic reasoning prevails, ask yourself: is it even worth to be humiliated by someone who comes to Malta to save – not spend! – money?

Venting anger is a physiological need in a setting of high economic pressure and social injustice. The universal tolerance is a poor response to the deepening inequality of opportunities and results. How can we pretend to treat the people, whose status and life conditions are profoundly unequal, in an equal way? Contrasting attitudes can be the basic act of justice, aiming to compensate for the abundance of privileges or the lack of them.

Do not keep “go back to your country!” to yourself but use it justly. Venting your anger towards the least privileged, the most vulnerable, the lowest levels of social hierarchy is too easy, not to mention unfair and unkind. Vent your anger with a purpose – channel it at the privileged representatives of corrupt institutions. Stand up for those in need of help – tell the parasites to go back to wherever they belong and tell them to quit tax avoidance for good.